THE PESHAWAR TRIBUNE

Volume 2, Issue 1 – Founded 1872

“THE ONLY NEWS THAT'S FIT TO PRINT”

Wednesday, April 18th, 1892

Editor’s Note – April 18th, 1892

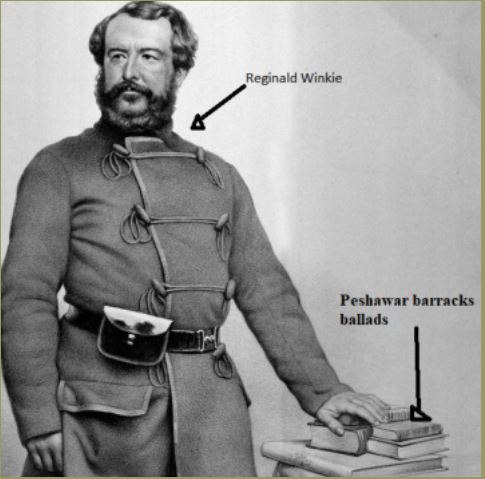

From the Desk of Mr. Reginald Winkle, Editor-in-Chief

It is with a mixture of grave concern and not inconsiderable pride that I present to our readers the latest field dispatch from Mr. Mortimer Harrington, our man in the North-West Frontier. Presumed missing for ten days, Mr. Harrington has once again defied both nature and bullets to deliver a report that is as vivid as it is perilous.

The courage shown by our correspondent — filing copy from a goat-sodden hut amidst the tribal uprisings of Kurram — is the very stuff of Imperial legend.

Though we fear for his safety, we cannot deny the surge in subscriptions that follows each of his dispatches.

May Providence preserve him.

And may his next article require fewer bullets.

— R. Winkle, Editor

[FIELD REPORT – CENSORED PRIOR TO PUBLICATION]

Approved by Lt. Col. Horace Blevins, Military Intelligence

Filed: April 12th, 1892

From: M. Harrington, Correspondent at Large

Location: Classified (Presumed – Upper Kurram Region)

Field Dispatch – April 12th, 1892

"There are times when the Empire forgets her sons. And there are times when we remember why."

To Whom This May Find,

Filed from the heights above a grim valley, in a house that smells of goat sweat and rifle oil.

The Pass burns with unrest. Below me sprawls the ragged camp of Mulehead, the self-styled Khan of the Waziri — a man neither savage nor civilised, but carved from the very stone of these hills. They follow him not for flags nor faith, but because he never flinches.

Opposing him lies the rebel Sharif the Ghazi, whose name is etched on bullets and blades alike. His voice speaks through two vile instruments: Habibullah the Butcher, a fiend in human shape, and Suleiman Khan, the Voice of the Sharif — whose sermons can ignite a village or bring it to its knees.

Both despise the ferenghees with a fury that time cannot quench. Yet Mulehead, fierce as he is, plots the liberation of one particular officer — Major-General Furthings, held in the hills, more token than trophy.

Mulehead's motives are his own. He fears not the Queen’s wrath, but the khaki-clad retribution that would spill into his precious valleys, disturbing his smuggling routes, his feuds, and whatever shadows he trades in.

I, Mortimer Harrington, once an esteemed Peshawar Tribune reporter, now merely a shadow in this land, observe it all. One would call this fate. I call it witness.

The rebel machine gun — cursed be its tongue of lead — commands the valley crossing. Mulehead’s ancient cannon, a rusting beast dragged by tired mules, waits for revenge. The warbands stretch and growl across the pass like a thundercloud clawing down the gorge.

From the house where a shepherd — whose name I shall never know — found me bleeding among the rocks and thorn, and nursed me with prayers to the Most Merciful, I watch the living myth of this land unfold. The kindness of that hillman, rough-handed and silent, is the only reason these words are written.

From the crags above Kurram Pass, I see them gather. Not in ranks, but in ripples — like a flood summoned by old gods. Waziri columns descend from the ridges with grim determination. This is no parade-ground war. It is movement born of memory and grievance. Men with rusted muskets and gleaming eyes, mules piled high with powder kegs and tins of opium, veiled women with rifles slung beneath shawls — all move as one breath, one storm.

Through field glasses, the sight is biblical: a pilgrimage of war. Porters bear crates and bundles like holy relics, beasts of burden trudge as if yoked to prophecy. This is no mere raid. This is the mountain’s fury, clothed in flesh and steel.

Their numbers swell with every hour. All signs point toward the rebel redoubt where the English general is held. If Mulehead means to free him, it is not for love of Empire, but to avert a reckoning that would scorch these valleys to ash. He may curse the Union Flag — but he curses more the boots that might trample his kin in its name.

The hills are restless.

The vultures circle early.

And the only law here is written in jezail smoke and the blood of old grudges.

God Save the Queen — if She still remembers.

— Mortimer Harrington, somewhere above Kurram Pass

Verses of Fire from Mulehead’s Camp

A Barracks Ballad by Reginald Winkle, Editor

Composed at the Peshawar Pressroom, 18th April 1892

In the heart of dust, beneath the golden sky,

Where the wind whispers and the echoes roar,

Three Khans stand tall, hearts of stone,

With gazes that defy both death and life.

The Khan of the peaks, the Khan of the sand,

The Khan of the river that never halts,

Fire burns in their fierce eyes,

Minds of war, hearts of lion.

In the center, the cannon, the heart of iron,

With its roar that shakes the earth,

A beast of death, armed with flames,

Under Mulehead’s hand, always ready.

The mules graze, patient and deaf,

Their shadows stretching across the barren ground,

Loaded with provisions, laden with strength,

Filled with life coursing through the sands.

The jezails fire in the twilight’s silence,

Smoke of powder, lightning in the wind,

Each shot a promise, an oath,

Each shot a lament that the night listens to.

The chora strikes, its edge keen and sharp,

As the blood of the rebels stains the earth,

Vengeance long awaited, now in full swing,

The Khans who turned must pay with their lives.

The banners rise, the call to arms,

The winds carry the cry of the fallen,

And soon, the English general, chained in shame,

Will taste the dust, freed by Mulehead's wrath.

The chora plays, sweet and bitter,

As dawn rises between the mountains,

And the caravan of camels and goats moves forward,

Under the watchful eye of the Khans, ever on the march.

Final Scene – The Clash

By the time this issue is printed, the battle will have been fought. And with it, the fate of General Furthings.

Between them, like a stone in the current, stood Mulehead, and with him, the Span Mules. They bore his red banners. Only scars and powder barrels. And that ancient cannon, blackened and rebored, which they called “The Old Mule.”

He did not shout orders. He nodded once — and wheels began to turn.

“Let Sharif pray to his machine gun,” said Mulehead, loading the first shell.

“Let the Ghazi see what fire truly means.”

The rebels had the range, but the loyalists had the will.

The cannon barked — a deeper voice than any jezail.

The time for words had passed. Now only powder would speak.

And as for the captured English general, they say his ears heard the first thunder, chained in a cave not far from the smoke.

And he smiled — for he knew that Mulehead had arrived.